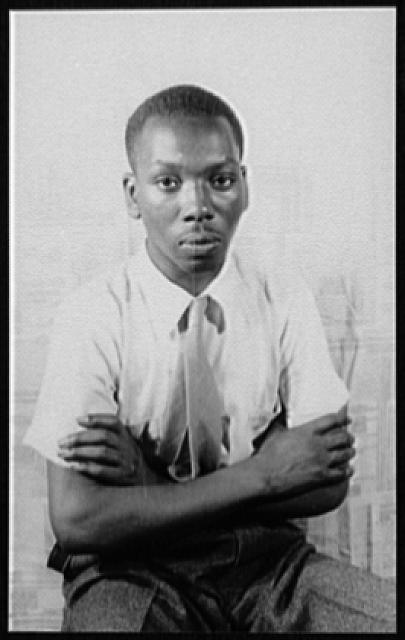

I wasn’t familiar with Jacob Lawrence and his art until this past fall, when Kate and I took a course through Tufts OLLI, their continuing education program, called “How Artists Look at Art”. Based on the book Portraits: Talking with Artists at the Met, the Modern, the Louvre and Elsewhere by Michael Kimmelman, long time art critic for the New York Times. Kimmelman went cruising museums with some of his pals, great artists from the 20th century, and recorded their comments and impressions, favorites and dislikes, influences and insights. I like the book, but mostly as a springboard for more research and understanding. Kimmelman isn’t a great writer, but he was able to get some famously reclusive and private artists to open up in front of other art. Our discussion group leader brought a ton of slides (on computer of course) to each session, and we dove in and explored these artists in depth.

Of all the artists we studied, Jacob Lawrence was my greatest revelation. How lucky is it, that this spring, the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA mounted an exceptional exhibit of his series, Struggle: From the History of the American People, the only one of Lawrence’s seminal painting series that was dispersed to multiple private collections and museums after its initial showing. PEM’s curators, working with colleagues from other American museums, located 25 of the 30 panels in the series, and working with collectors and institutions, brought them together for the first time in 63 years. Seeing these works in person, displayed together as they were originally conceived, cemented my feeling that Lawrence was an extraordinary artist and storyteller. Don’t believe me? Here is Sebastion Smee’s review in the Washington Post:

“Struggle” is a national treasure. It is a work of sustained brilliance by one of America’s finest artists working at the height of his powers. Even though Lawrence originally planned 60 panels, and even though, of the 30 he painted, five have gone missing, the art testifies to a level of ambition that still astounds.

Sebastian Smee, Washington Post, January 24, 2020.

Lawrence created over 300 works throughout his career, including narrative series on the Haitian general Toussaint L’Ouverture, leader of the Haitian Revolution, Fredrick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, and abolitionist John Brown.

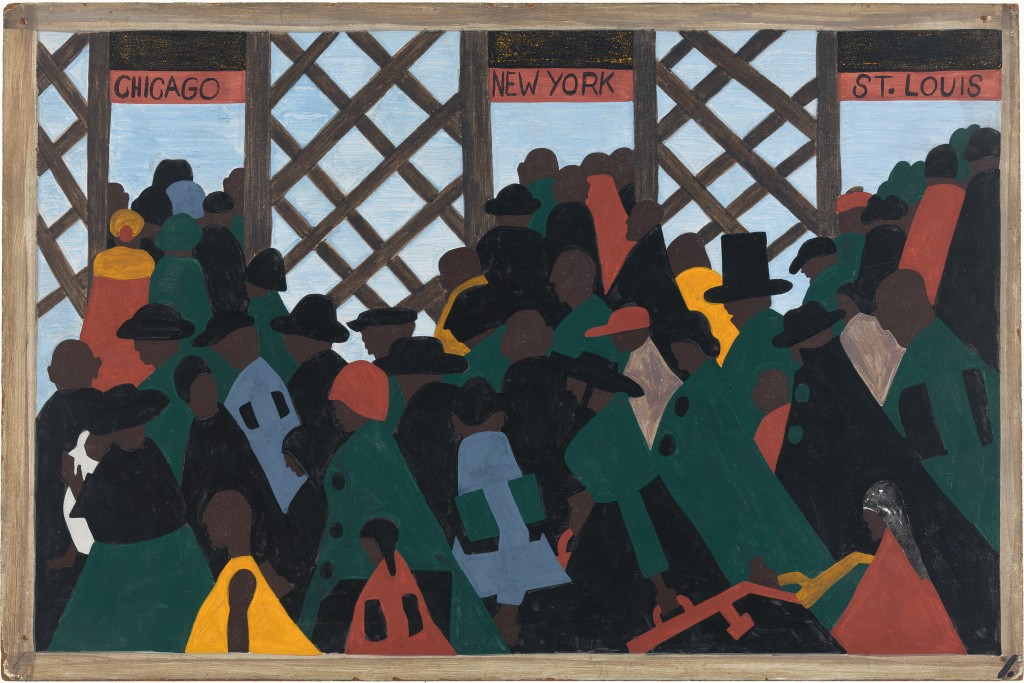

In 1941, 23 year old Lawrence completed his Migration series about the mass exodus of African Americans from rural southern states to northern cities during World War I. His work was instantly recognized as a masterpiece, acquired in toto by MoMA and the Phillips Collection in Washington DC who split it up between the institutions, with MoMA acquiring the even numbered panels, and Phillips Collection the odd numbered ones. Fortune Magazine published an article while the series hung at New York’s Downtown Gallery, including 26 of the 60 panels, catapulting Lawrence to instant fame.

What attracts me most to Jacob Lawrence’s work is his brilliant adaptation of 20th century artistic styles to dramatize his subject matter and tell his stories. In his sharply outlined color blocks, I see the influence of Matisse. Look at how his faceted, angular shapes in Cubist style, serve to make his painting vibrate with rhythmic motion. The violence and intensity of this slave rebellion in Struggle, Panel 5 is portrayed through vivid colors and the flash and sharp thrusts of weapons and the bursts of blood red spilling down the panel, harnessing Cubism’s deconstructive force to strip away all but the emotion of resistance and … Struggle.

Another example, Struggle, Panel 9, shows the bleak winter of retreat to Valley Forge after the Continental Army’s crushing defeat by British forces at Philadelphia in 1777. A cluster of figures huddles against the cold of blue snow, backs bent away from us and the dying horse. The figures are just angled shapes, indistinct, but still sharp. Their sloping angled shoulders depict their resignation. Almost abstract, this painting distills feeling into pure form and compels us to experience.

While Lawrence created his own unique style and vision, he was influenced by artists depicting the history of other marginalized and oppressed people through raw, emotion-packed narrative paintings. He was especially fond of the Mexican muralists, such as Jose Clemente Orozco. I see a strong connection to Orozco’s work in Lawrence. I can’t help but imagine he was also influenced by Picasso’s Guernica, one of his most famous works, painted in 1937 and depicting the horror of war, including weapons, a gored horse, and agonized victims.

Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Lawrence was fascinated by workers, tradesmen, builders, people who worked with their hands, and the tools of creation and physical labor. He created many images showing the dynamic movement and power of people creating things with tools, using his trademark saturated colors and angular Expressionist/Cubist style. He also showed the everyday life of Black people in his neighborhood in Harlem, such as The Visitors, depicting a family’s vigil over a sick loved one’s bedside and in the parlor outside the bedroom. His work straddles representation and abstraction, stripping out everything except the strength and dignity of his subjects.

Sometimes, modern art, especially abstract art, can seem unemotional, esoteric and elitist. Other modern and contemporary artists are so focused on making a political statement or capturing the mood of the present that they seem to be speaking only to a narrow audience at a point in time. Jacob Lawrence is an antidote. His art is absolutely of our time, stylistically indebted to modern art history. Lawrence captures and narrates the world of African Americans and their place in American history with a unique perspective focused on their lives, but mostly muting the strident, overtly political message of the civil rights movement in favor of more universal themes of justice, dignity, and historical presence and impact. He set out to describe the essence of Black experience through our history, and let it speak for itself. We’re lucky that he was such an exceptionally talented artist that this humanity and vision leaps off his panels and becomes part of our own experience.

The exhibition “Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle” runs until the end of April at PEM. I hope they extend its run there so that we can see it again, after the COVID-19 closure of the museum to the public. From PEM it will go to the Met in New York from June to September 2020, then to the Birmingham Museum of Art from October to January 2021, on to the Seattle Art Museum from February 2021 to the end of May 2021, and then finally to the Phillips Collection in Washington DC, from the end of June 2021 until mid-September. If you happen to be near this exhibit in your travels, I recommend making a special effort to see it.

For more reading:

A lengthy interview with Jacob Lawrence in 1968 – transcript. In “Archives of American Art, Oral History Interviews”

The best of “Ask Joan of Art” on Jacob Lawrence, 2011, Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“Jacob Lawrence’s Art as Journalism”, Syreeta McFadden, 2016, The Nation.

Photo credits:

Lawrence, Struggle Series – I took those photos at PEM.

Photo of Jacob Lawrence – Library of Congress, public domain. From Wikimedia Commons.

Migration series panel 1 – MoMA’s interactive site on the whole series. Used under fair use principles.

Orozco and Picasso images – from wikiart.org under fair use principles.

Lawrence, “The Builders” and “The Visitors” – from artsy.net under fair use principles.